Intellectual History or the History of Ideas?

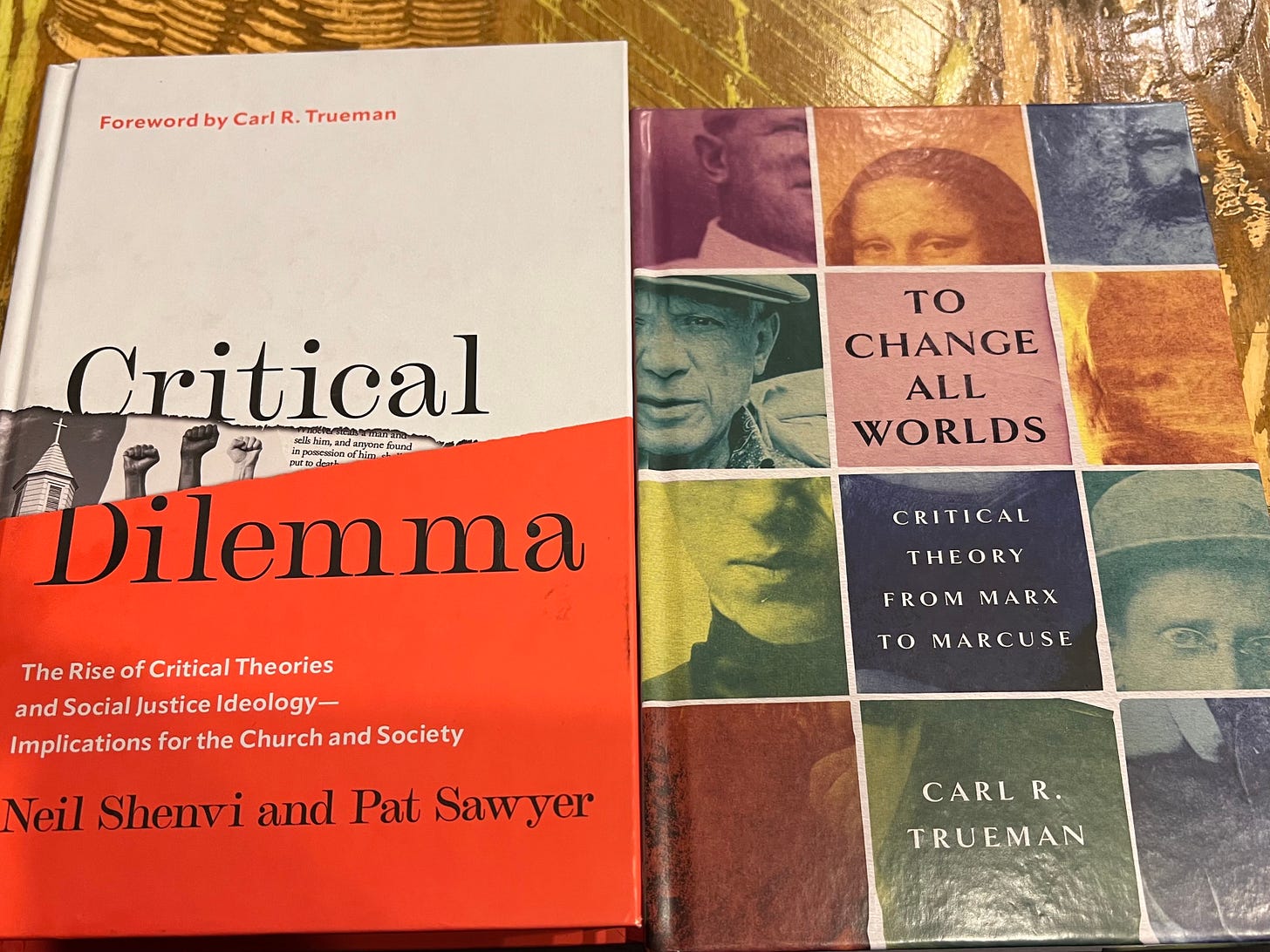

I hope to finish Shenvi and Sawyers, The Critical Dilemma and Trueman’s, To Change All Worlds before Christmas.

Carl Trueman’s description of the work of an intellectual historian has already proven insightful. I attended a talk this week at the Evangelical Theological Sociery. One of the speakers described himself as an intellectual historian—a term I had never encountered before. Trueman explains that an intellectual historian studies how ideas and schools of thought come into being. They analyze the claims these ideas make about the world in which we live and their cultural, intellectual, historical, and ideological significance. Importantly, the intellectual historian is not as concerned with whether an idea is true or coherent as they are with its historical and cultural impact.

Trueman is a scholar of the first rank, and I think intellectual history is an important field, but it has its limitations. For instance, an intellectual historian cannot make claims about the truth or falsehood of theological systems. Nor can they offer moral judgments about historical figures. Instead, their work involves exploring the motivations of historical actors—a practice that Wimsatt and Beardsley critique in The Verbal Icon (1962). They argue that efforts to uncover authorial intent fall into what they call the intentional fallacy, warning against confusing speculation about an author’s motives with the meaning of their work. Similarly, intellectual historians cannot prescribe what ought to be but are limited to describing what is. Their work is largely interpretive and contextual, not evaluative or normative.

This brings me to Wimsatt and Beardsley’s discussion of the intentional and affective fallacies, which I find particularly compelling. When we discuss authorial intent, we often assume we can reliably discover the meaning of a text by reconstructing the author’s motivations. However, C.S. Lewis vigorously opposes this view in Modern Theology and Biblical Criticism. He writes:

"All this sort of criticism attempts to reconstruct the genesis of the texts it studies; what vanished documents each author used, when and where he wrote, with what purposes, under what influences—the whole Sitz im Leben of the text. This is done with immense erudition and great ingenuity. And at first sight it is very convincing. I think I should be convinced myself, but I carry around with me a charm—the herb moly—against it."

Lewis continues:

“Until you have been reviewed yourself you would never believe how little an ordinary review is taken up by criticism in the strict sense: by evaluation, praise, or censure, of the book actually written. Most of it is taken up with imaginary histories of the process by which you wrote it. The very terms which the reviewers use, praising or dispraising, often imply such a history. They praise a passage as labored; that is, they think they know that you wrote the one currente calamo and the other invita Minerva.”

And he concludes:

“The reconstruction of the history of a text, when the text is ancient, sounds very convincing. But one is sailing by dead reckoning; the results cannot be checked by fact. In order to decide how reliable a method is, what more can you ask for than to be shown an instance where the same method is at work and when you have facts to check it by? … The assured results of modern scholarship as to the way in which an old book was written [getting at the author’s motivations], are assured, we may conclude, only because the men who knew the facts are dead and can’t blow the gaff.”

Put simply, you can speculate all you want about the motivations and influences of an author and even make it sound convincing, but in the end, it’s pure conjecture.

I write this not as a critique of Trueman but as a response to the talk I attended, where the intellectual historian dismissed the history of ideas as too focused on the meaning and origins of texts, as well as their coherence and truth. Instead, he argued that the intellectual history of theological systems is more valuable.

As I see it, the history of ideas is far more grounded in facts. It prioritizes the truth and coherence of ideas, whereas intellectual history leaves too much in the hands of the historian, relying heavily on speculation about influences, motivations, and significance. While intellectual history has its place, I find it less reliable because it often depends on methods that cannot be checked against reality. For me, the history of ideas remains the firmer foundation.

Still, I ordered a book from Amazon to learn more about intellectual history…